This post is by guest blogger Anna Fialkowska

The prevalence of anxiety disorders, including Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorders (OCD), Social Phobias, Specific Phobias, Panic Disorders and Post-traumatic stress Disorder (PTSD) are significantly rising. Increased awareness and availability of effective diagnostic tools and services specialised in diagnosing and treating the aforementioned conditions has unquestionably led to more individuals being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Although all of the conditions are characterised by unhelpful thoughts, an exaggerated perception of fear and increased levels of stress, they are all highly distinctive conditions impacting individuals in a highly varied manner (Papworth & Marrinan, 2019).

What is Panic Disorder?

Panic Disorder is a condition characterised by recurrent attacks of severe anxiety, known as panic. Although it can vary between individuals, panic attacks are usually unpredictable and are not usually restricted to any particular situation. Panic involves a sudden onset of strong physical symptoms, such as heart palpitations, increased body temperature, sweating, dizziness, choking sensations or feelings of unreality (depersonalization or derealization). Those physical symptoms are often accompanied by a catastrophic interpretation, such as a belief that the person is having a heart attack, that they are going to faint or that they may die. The perception of going mad and losing control is also a highly common symptom. However, all of these symptoms are associated with the fight or flight response, our natural reaction to danger. Specifically, when the fight or flight response is activated, levels of adrenaline increase to prepare our body to face danger. This leads to strong physical symptoms including increased temperature, perspiration, and heart rate, many of the symptoms characterising panic. This shows us that panic is not an indication of illness or physical abnormality but it is a ‘faulty alarm system’, which tells our body that we are in danger, even though there is no evidence for it (Bennett-Levy et al., 2010).

How do we cope?

Individuals who experience panic attacks are often coping by avoiding situations like those that caused previous panic attacks. For instance, driving or going shopping to a busy shopping centre, may become associated with such attacks. Although the avoidance almost immediately reduces distress as we are no longer exposing ourselves to a stressful situation, it makes the anxiety significantly worse over the long-term. The longer we avoid stressful situations, the more unwilling we are to confront them and the more we confirm to ourselves that panic attacks are dangerous, that something bad is going to happen and that we should avoid specific places or situations. Due to this avoidance, we are minimising opportunities to disconfirm our catastrophic predications. This leads to increased anxiety that is often generalised to other situations, a chain of events known as the vicious cycle of anxiety which can last for years without support. However, we can stop this vicious cycle by exposing ourselves to the feared situation or places associated with panic (Papworth & Marrinan, 2019). The following processes can help in the treatment of panic disorders.

Habituation

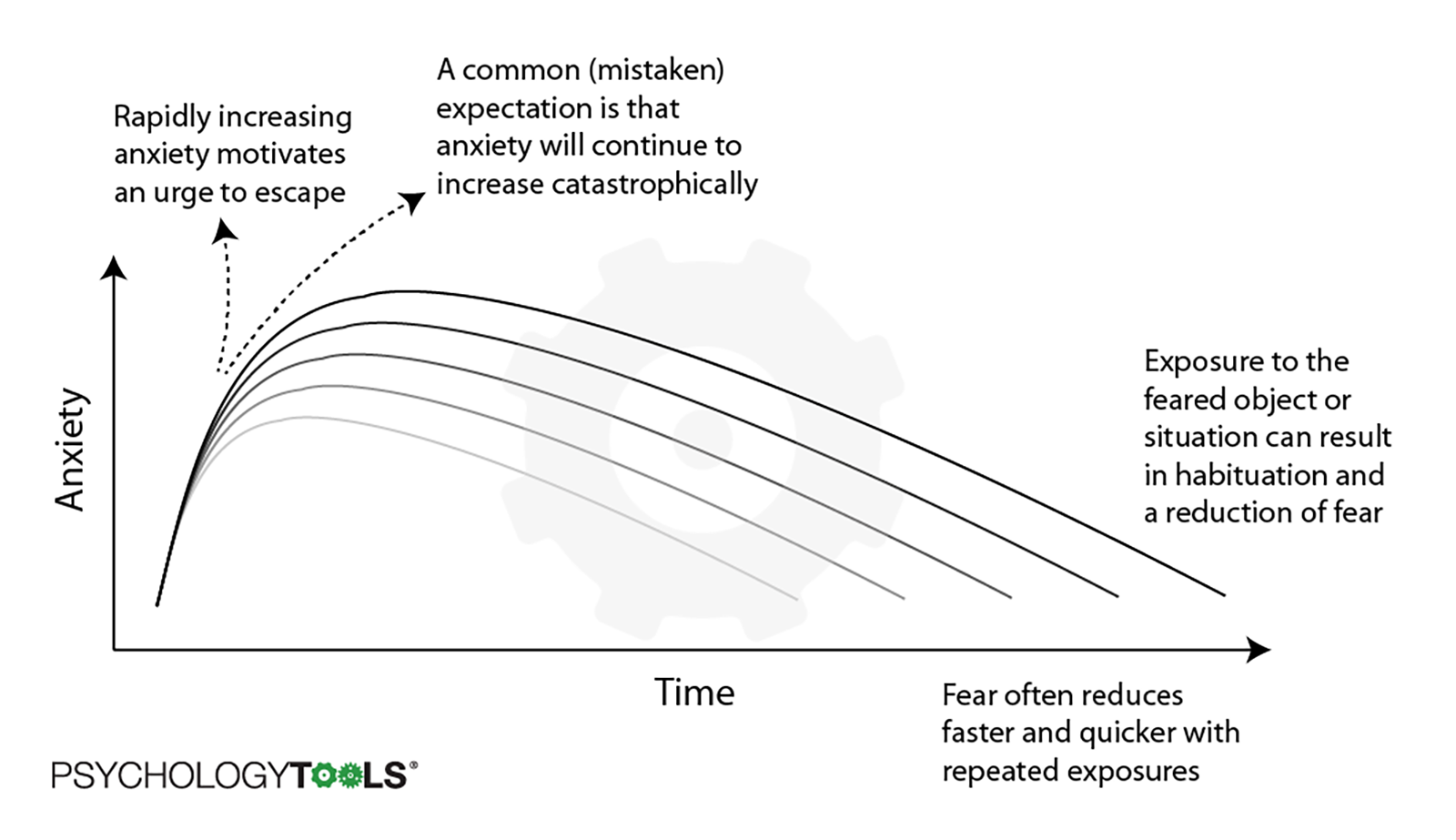

Habituation is a natural reduction in arousal that occurs when we allow ourselves to remain in the presence of a feared situation for a prolonged period of time. Over time, anxiety reduces gradually whilst we remain in contact with the feared stimulus. This is highly different from avoidance in which arousal reduces sharply but only when the person escapes from the feared situation. The problem with repeated avoidance is that the fear remains the same and we are confirming our catastrophic thinking. The next time we come across the feared stimulus, our arousal levels will be the same as before. In exposure, habituation means that subsequent exposure sessions provoke less anxiety than previously. The process of habituation is illustrated by the graph below.

Graded Exposure

Graded Exposure is a technique based on the process of habituation that is used to manage symptoms of panic disorder. It involves exposing ourselves to feared situations or places that are associated with panic. The more we expose ourselves to those situations, the less anxiety we experience. However, for the exposure to work it needs to be:

- Graded - we should gradually expose ourselves to a feared object or situation, starting from the easiest situation and gradually building upon this in a manageable way.

- Prolonged -we need to stay in the situation till the anxiety level is significantly reduced.

- Repeated - it needs to be repeated till we feel comfortable in the situation.

- Without distraction - we need to experience some level of anxiety for the exposure to work. Therefore, we should limit any distractions, such as listening to music or talking on the phone.

The Efficiency of Graded Exposure

Graded Exposure has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of specific phobias and panic disorder (Grös, & Antony, 2006). However, the dropout rate can be relatively high due to the stressful nature of such approaches. Alternatives to the traditional in-vivo approach (real-world confrontation of feared stimuli) are now being explored, offering more options for treatment. For instance, an imaginal approach involving virtual exposure therapy was shown to be effective for the treatment of arachnophobia (Michaliszyn et al., 2010). This approach uses virtual headsets to introduce stimuli to individuals and has shown much success since its introduction. However, innovative approaches are costly and access remains limited. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that in-vivo exposure is more effective than imaginal approaches, providing strong support for the currently applied interventions (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). Both, however, provide opportunities to aid individuals in managing their condition, overcoming panic disorders and increasing wellbeing in the process.

Contact us today to see how Sparta Health can help provide mental health and wellbeing support.

About Anna Fialkowska

Anna Fialkowska is a Trainee Health Psychologist, is completing her doctoral training at the University of the West of England and currently works as a Heath Improvement Practitioner. She has worked within the field of mental health dysfunction and cognitive rehabilitation over the last six years. Her main areas of research include the development of behaviour change interventions, the impact of stress on individuals’ physical health and the effect of chronic conditions on psychological well-being.

References

Bennett-Levy, J., Richards, D., Farrand, P., Christensen, H., Griffiths, K. G., & Kavanagh, D., et al. (Eds.). (2010). Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grös, D. F., & Antony, M. M. (2006). The assessment and treatment of specific phobias: a review. Current psychiatry reports, 8(4), 298–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-006-0066-3

Michaliszyn, D., Marchand, A., Bouchard, S., Martel, M. O., & Poirier-Bisson, J. (2010). A randomized, controlled clinical trial of in virtuo and in vivo exposure for spider phobia. Cyberpsychology, behavior and social networking, 13(6), 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0277

Papworth, M., & Marrinan, T. (2019). Low intensity Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (2nd ed.). London: Sage.